How to NOT Stress About COVID-19

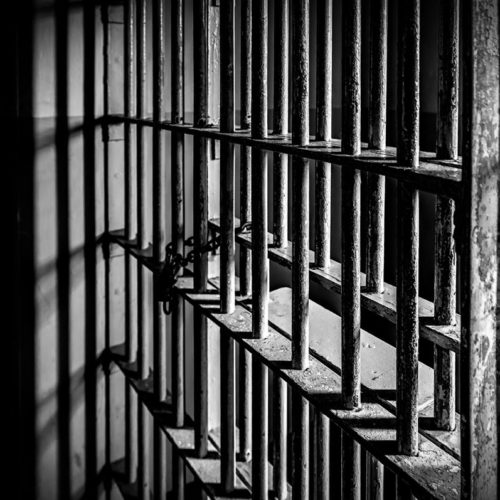

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, millions of people were left homeless. The correctional facilities faced a rather comic scene: tens of inmates with orange jumpsuits crowded on roofs or highways, watching the deluge on the street flood away their jail ceils and former homes, while the police hold giant rifles to guard against their escape.

Even today, you could still see dilapidated bones of homes left unkempt in mid-town New Orleans, one of the most impoverished parts of the city. Meanwhile, the historic French Quarter was quickly rebuilt, boasting its European-style houses and jazz bars for millions of tourists each year.

When disasters like Katrina and the Coronavirus hit, it is always the people who are of the lowest socioeconomic status who are hit the hardest first. Yet we barely have time to care about their plight because heck, we ourselves are impacted too! We have our own health to take care of, but more often than not, it is our mental health that need to be taken care of. In other words, from a privileged standpoint, it is our isolation, loss of liberty, and disruption of routines that we lament over instead of the concrete food-or-hunger, life-or-death issues that many others are struggling with.

I spent a lot of time lamenting in the first few weeks of the coronavirus outbreak. For me, the disaster seemed to hit right when my trajectory at Columbia was beginning to unfold: my criminal justice organization was starting to gain traction on campus, I was steadily building professional connections, excited about my summer internship in Israel, and making genuine friendships with people I care about, and… boom. All plans were disrupted in the short span of two weeks.

Like many people, I struggled with anxiety, fear, even paranoia, and a disillusionment of craving things to be normal again. In the next phase, I tried to regain normalcy by getting in to a new routine: waking up at 5 am to workout, reading, cooking, learning new skills, sleeping at 9 pm… I believe that many people are building their new life in they own ways, and I am heartened to see this. For me, this new routine alleviated my fears (at least of unproductivity), but my nostalgia for “better times” persisted.

A few days ago, I read about news articles of jails as petri dishes for coronavirus. Indeed, when Purell is contraband, how does one follow public safety guidelines? That is why we are seeing the tragedy of prisons where one confirmed case means the infection of hundreds of inmates, with 2,500 known deaths in the prison system across the country (as of April 2020).

I thought about my former clients in the Orleans Public Defenders, where I interned at last summer. Were they released or still incarcerated? Truth is, in my pursuit of personal achievements, I had never followed up on how they were doing. Chances are, even if they were released, they would not have a stable home or income to protect themselves against the coronavirus.

I felt ashamed. I had started Criminal Justice Coalition in order to support people who are incarcerated, but in a time of their most need, I chose to hide away in my own isolation, oblivious of that of others that are far more grounded in the reality of danger as opposed to a perception thereof. It had been a month since Criminal Justice Coalition provided any direct support to people in the community, and this must end. Yesterday, I spent the whole day (re)-connecting with people in public defense offices, legal aids, prison education projects, and my own organization to coordinate our way forward. Some actions that are in urgent need are:

- Advocate for releasing people from jail, especially those charged with nonviolent crimes

- Fundraise for public defender offices, where many attorneys and social workers are not getting paid; many public law offices are funded by traffic tickets, so there is no funding when entire cities are in lockdown

- Help the voices of people in the criminal justice system under coronavirus get heard

……

We do not yet know where our student organization can help with the most, but the direction is clear. Personally, I have already seen that the drive to positively impact people who need the most help facing the pandemic has, all at once, lifted me from the lamenting; because I could see more important issues than those of my own, waiting to be solved. In this sense, my motivation may be a little selfish, but sometimes when we become compassionate towards others, it uplifts our own spirit as well.

Often, when we suffer from negative emotions related to outside factors that we cannot control, what we are really suffering from is a constraint of perspective; of a failure to see through the few things that are immediately relevant to us and empathize with those who we may have nothing in common with, but whom we are ultimately able to connect with because of our shared humanity. When we expand our perspective, perhaps we’d be able to contextualize our struggles in the broader state of human affairs — and better, make an impact in it.

For those who are experiencing unwanted negativity with regard to the pandemic, I am sharing this to nudge you to expand perspectives into the wider world instead of shirking to the corner of our own room. Get up and do something for others. Try to understand and make a change in other people. It does not have to be something related to criminal justice or even social justice, but a simple act of empathy that shifts our worldview into a wider one.